Introduction

Enacted 150 years ago in 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment established that the right to vote could not be denied on the basis of race. Yet African Americans, particularly those residing in southern states, continued to face significant obstacles to voting. These included bureaucratic restrictions, such as poll taxes and literacy tests, as well as intimidation and physical violence.

Little was done at the federal level to enforce Reconstruction Era laws, including the Fifteenth Amendment, until the mid-twentieth century. Even after the passage of civil rights bills, discriminatory practices depressed voter registration rates for African Americans living in the South. When civil rights activists organized a voting rights campaign in Alabama in 1965, it culminated in violence on March 7 when Alabama state police brutally attacked peaceful marchers in Selma. The event caused an outpouring of support for a bill protecting the right to vote for all Americans.

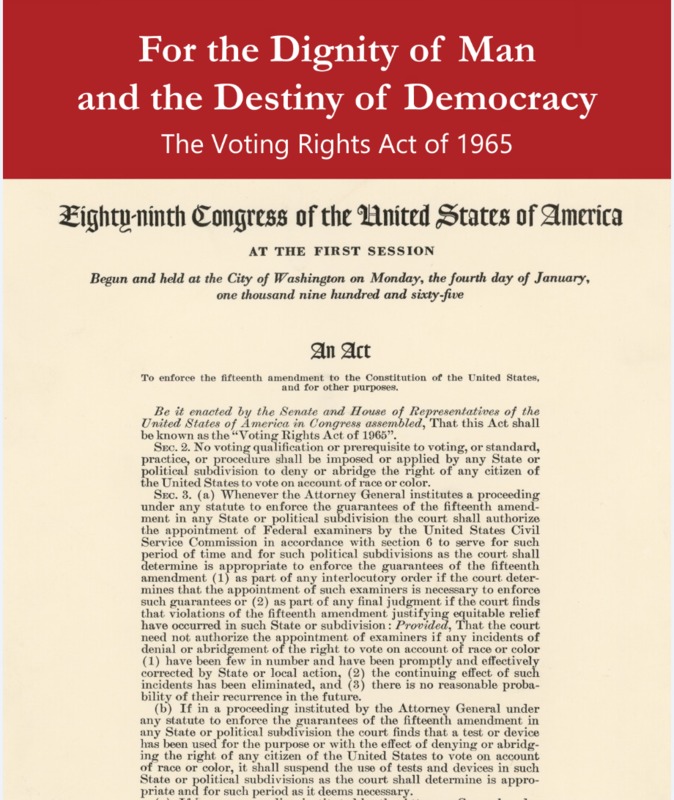

The President addressed a joint session of Congress on March 15, calling on them to pass a voting rights bill. He opened his speech explaining that he spoke "for the dignity of man and the destiny of democracy." The Administration sent a proposed bill to Congress two days later, and though it had strong bipartisan support, Congress spent several months debating various aspects of the legislation. In August 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law, finally fulfilling the promise of the Fifteenth Amendment.